Humans move tremendous amounts of earth annually. They are arguably the premier geomorphic agent sculpting the surface of Earth today

Every year humans move about 0.8 Gt (Gt = gigatons, or 1 billion tons) of earth in house construction, 3.2 Gt in mineral production, and 3 Gt in road construction. If all this earth were dumped into the Grand Canyon, it would fill the canyon in about 400 years, or about 0.01 percent of the time it has taken the Colorado River to carve it! Such a comparison is not so far-fetched as one might think. A common method of coal mining in West Virginia today is mountain top removal (Fig. 1). To gain access to coal seams at depth, entire mountain tops may be unceremoniously shoved into adjacent valleys, filling the valleys. If we scale this earth moving to the world as a whole, the total earth moved by humans is estimated to be 30 to 35 Gt every year. For comparison, meandering rivers may shift 25 to 40 Gt of sediment from one side of the river to the other during a year, and other geomorphic processes move much less material.

About 3500 Gt of soil are moved annually in plowing. Most of this, however, is simply transferred from furrows to ridges, and is then washed back to fill the furrows; no permanent landform is created. On the other hand, about 75 Gt/y is actually eroded from the plowed fields by wind and water. Most of this is deposited only a short distance from the field on slopes and in floodplains, but up to 10 Gt/y may be transported all the way to the oceans. One ecologist estimated that soil was being removed from farm fields at 17 times the rate at which it is being formed by weathering processes, an estimate that does not bode well for the long term viability of the world’s food supply.

Of course humans have not always been such prolific earth movers. The earliest archeological record of humans earth moving is from 40,000 years ago when Homo erectus was making sizable seasonal dwellings with walls supported by boulders moved into place for the purpose.

Thereafter, milestones in the motivation and ability of humans to move earth occurred in the Mesolithic, about 7000 B.C., when the hunter-gatherer way of life gave way to farming and village life; about 3000 B.C. and 1500 B.C. at the beginning of the Bronze and the Iron ages, respectively, when the desire for minerals led to expanded mining, and metal tools facilitated earth-moving activities; about 1800 A.D. when steam power and the Industrial Revolution led to a need for coal and at the same time provided machinery for mining coal and other earth-moving endeavors, and finally in the early 1900s when the internal combustion engine eventually led to the humongous excavators of today, some of which can pick up 30 tons at a swipe.

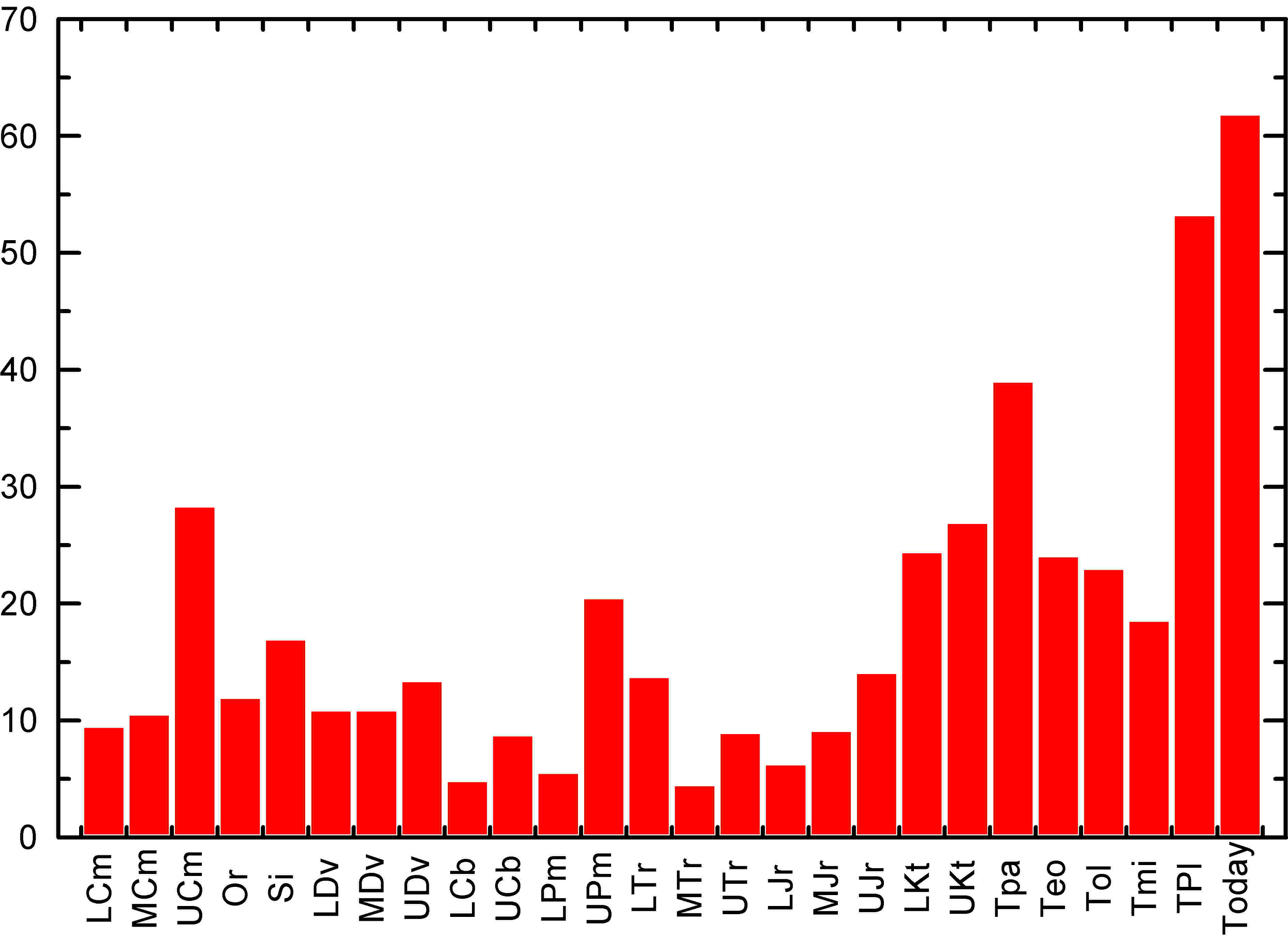

To examine sediment fluxes over a still longer time, Bruce Wilkinson has estimated sediment fluxes to the oceans over the past 500 million years by looking at the volume of sedimentary rock preserved in the geologic record (Figure to the right). The present is an unusual time in Earth's history.

Selected References

Hooke, R. LeB., 1994, On the efficacy of humans as geomorphic agents: GSA Today, v. 4, No. 9, p. 217, 224-225.

Hooke, R.LeB., 1999, Spatial distribution of human geomorphic activity in the United States: Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, v. 24, p. 687-692.

Hooke, R.LeB., 2000, On the history of humans as geomorphic agents: Geology, v. 28, p. 843-846.

Wilkinson, B.H., 2005, Humans as geologic agents: A deep-time perspective. Geology, v. 33(3), p. 161-164.