see photos below

Leigh is back in Maine and files this report on the field season:

I had to break this journal entry up into ‘The Science’ and ‘The Life’ because scientifically everything went smoothly – the difficulties came from everyday life activities.

The Science

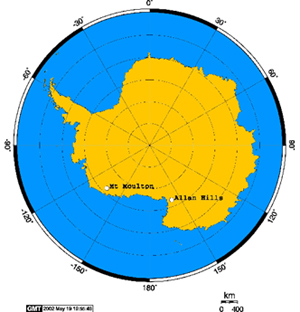

Our objectives at the Allan Hills were similar to those at Mt. Moulton – to study the ice flow and gather information for a potential horizontal ice core (refer to our projects page). Our tasks are outlined below:

- Mapping: The first 3 days were spent mapping the area so that we could figure out the topography and, consequently, the direction of ice flow. With GPS antennas attached to the snowmobiles, we drove around in grids and then zigzags to collect as much data as we could.

- Ice Flow: After we mapped the area and got a general idea of the ice flow direction, we installed ~20 ice velocity poles - 3m conduit pipes drilled into the ice. We determine their exact position with GPS and then resurvey them in the future to measure their displacement. The poles that we installed expanded an already existing network of poles that Blue installed in 1997 and that he and I resurveyed in 1999.

- Ice Core: Accumulation rates are an important variable in glaciology, yet they are difficult to measure. The method that we use is called beta counting. We try to identify radioactive horizons within the ice core (using a beta counter back in Maine) – namely 1955 and 1964 bomb tests. If we know the age of the ice at a certain depth we can deduce what the average accumulation rate for the area is.

- Radar Mapping: While Andrei, John and I put in the ice flow poles and collected the ice core, Blue collected radar data. The shallow radar is a small unit and can be easily dragged behind a snowmobile. There is already a bed topography map of the Allan Hills, so we didn’t need to do any deep radar mapping.

- Tephra Mapping: There are a couple of pictures of me and Andrei mapping the tephra layers. While I mapped the layers, Andrei collected tephra samples. These tephra layers were significantly smaller than the huge ones we saw at Mt. Moulton.

- Electronator: There are many more tephra layers in the ice than the ones that Andrei and I mapped by sight. To try to locate these layers John used his ‘electronator’. Two electrodes are attached to a wood bar that we drag behind the snowmobile. As we’re driving, the electronator measures the conductivity of the ice. This is a new invention of John’s and we were excited to test it.

- Meteorites: We did collect a few meteorites while we were in the Allan Hills. These will be used to date the surrounding ice (through the radioactive decay of cosmogenic nuclides). Unfortunately we did not collect more because of time (and temperature) restraints.

Don’t be fooled by the sunny pictures you see on the website! We all agreed that the Allan Hills was probably the most brutal place we’d been to (this is coming from 4 people who have done extensive field work in Antarctica, Svalbard, Greenland, Finland and Kamchatka). It was beautiful, but the weather that late in the season was tough. The brisk temperatures (-24°C) and light breeze of the katabatic winds (30 knots) were relentless and made everyday living pretty difficult. Here are two examples:

- Task 1: get out of your sleeping bag

- Ignore the thin layer of ice that has coated your sleeping bag from condensation of your breath.

- Ignore the fact that you can hardly talk with your tent-mate because the wind is flapping the tent so loudly.

- Take contact lens case out of your hat. If contacts are defrosted put them in. If they are still frozen, stick them in your armpit.

- Pull insulated windpants over fleece pants over long underwear. Add two polypro shirts on top of your base layer. Put on down jacket. Put on Antarctic issue down jacket (yes, I did have two down jackets on!), two pairs of socks, boot liners and boots. Top it off with a turtle neck liner, wind-stopper balaclava, goggles and hat. Put on your gloves and mittens. Okay, now you’re ready to go outside.

Despite the tough weather, we all managed to maintain our spirits and stay focused on our science goals. It became quite amusing how persistent the bad weather was. Usually you get one or two days of weather like that an entire season…we had it for 10 days straight.

February 7, 2004

The team only had a short time in McMurdo before they headed home. Andrei was able to send some photos.Click on a picture to see it full size.

This project is supported by a grant from NSF Office of Polar Programs

This project is supported by a grant from NSF Office of Polar Programs