Climate Change Institute

The chemical climate of Earth has particular relevance because nutrients and toxins are part of the burden in the atmospheric and hydrosphere. Many toxins have been added in quality and quantity to our environment through human activity, including agriculture, earth-surface disturbance, smelting, and the burning of fossil fuels. One of the more toxic elements of concern is mercury (Hg). This naturally occurring element has several unique properties that make its distribution and abundance problematic. It may occur as a liquid at earth-surface conditions, thus it is quite volatile. It occurs in a vapor stage in the atmosphere and thus can spend years in the atmosphere. It is released during the combustion of fossil fuels (especially coal). It is easily cycled between water, air, and soil. Most importantly, it is biomagnified in the food chain. Its abundance in water is commonly less than 10 nanograms per liter (one part in a billion billion). Uptake by algae typical results in an enrichment of about 100X; grazing of algae by zooplankton may produce an additional enrichment of 100X. Finally, fish may accumulate Hg from zooplankton to the point where the Hg exceeds 1 milligram per kilogram (one part in a million). Such fish are not suitable for human consumption and may be injurious to other predators, such as birds.

An important aspect of the biogeochemistry of Hg is the answer to the question: What has the flux of Hg been through time? or Have humans seriously impacted the biogeochemistry of Hg?

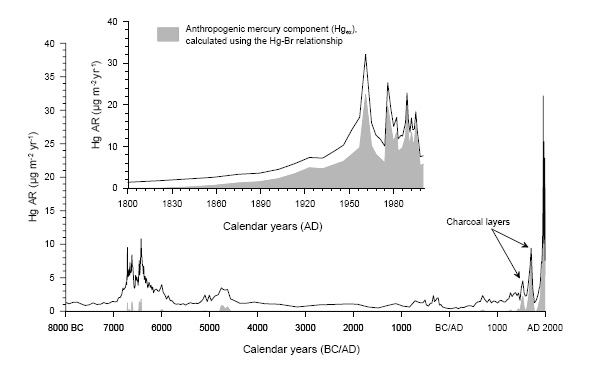

The figure above shows the accumulation rate of atmospherically deposited Hg at Caribou Bog, Orono, Maine through the last 10,000 years (the entire Holocene). The data are derived from the chemical and radiological analysis of a 5-meter long peat core (Roos-Barraclough et al., 2006). The solid line shows that the accumulation rate has been highly variable through time, largely due to differing plant communities interacting with the atmosphere at different times. In the last 100 years (small panel), the accumulation rate has reached unprecedented values, peaking in the 1970-1980 period, and then declining toward pre-industrial values as emissions of Hg have been identified and reduced. Thus this historic perspective enables us to place modern pollution by a naturally occurring toxin in perspective, and to identify current trends. The atmosphere is actually cleaner now than in the late 1900s. Lead, another toxin shows an even more dramatic improvement, with current atmospheric deposition rates at less than 5% of the 1970s maximum.