Paleoecological studies of Maine lakes reveal dramatic and continuous changes in water depth and vegetation since the retreat of glacial ice. Paleoecology Research Laboratory scientists examine biological remains preserved in lake sediment and physical properties of the sediment to determine environmental changes through time. Pollen and seeds reveal vegetational shifts, insect remains provide evidence for temperature changes, and sediment characteristics indicate rising or falling lake levels.

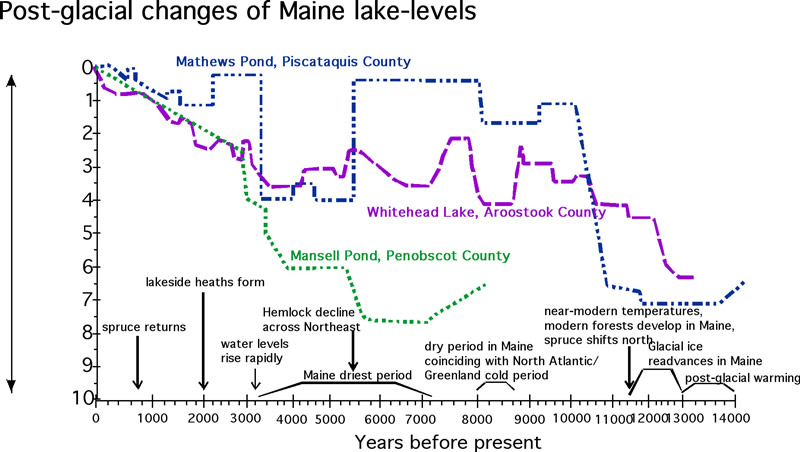

The results of University of Maine research demonstrate that Maine's current vegetation and lake levels are of recent (past 750 years or so) origin. Since the end of the ice age, Maine's water levels have constantly changed, but were consistently below modern levels, sometimes by as much as 4-8 meters. Forest structure likewise changed in conjunction with major climate shifts. Spruce trees, for example, were largely absent from the Northeast for more than 10,000 years from the end of the ice age until the climate became wetter and cooler over the past 2000 years. A massive hemlock die-off in the Northeast around 5500 years ago, from which hemlock abundance never entirely recovered, was probably linked to a drier climate. Our research suggests that Maine's water balance is tightly linked with temperature changes in the North Atlantic Ocean. Observed vegetation and lake-level changes in Maine correspond with those observed in studies by other researchers across New England and adjacent Canada.

Maine's current environment is unlike anything seen since the ice age. This has significant implications for Maine's resource based industries, including agriculture and the forest products industry. By demonstrating the state of Maine's water resources and forest composition under different climate regimes, our research can help state agencies and industry prepare for future climate changes.