Skip navigational links The Hunter-gatherer Spectrum in New Guinea

Principal Investigator: Paul Roscoe

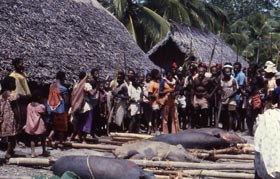

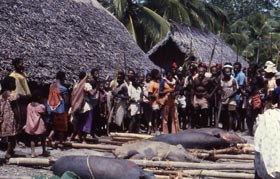

Photos for illustration purposes only are of Yangoru Boiken, a horticultural group (not a hunter-gatherer group) living in the East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea.

At the time of European contact, perhaps two million people lived on the island of New Guinea, speaking some 1000 languages and many more dialects. New Guinea is thus one of the most important regions of the world for cross-cultural research on non-state forms of social organizations and culture.

It has long been supposed that New Guinea is a land of cultivators. New Guineans were among the first peoples on Earth to cultivate crops, and at contact a majority were either horticulturalists, cultivating root crops such as taro and yam under long-fallow regimes, or agriculturalists cropping sweet potato under intensive cultivation regimes. However, a close examination of the ethnographic record – in particular, of unpublished and non-English language sources – has revealed numerous references to the presence of “hunters and gatherers.” The record suggests, in fact, that some 10-20 New Guinea societies were almost entirely dependent on wild foods at contact; another 20 or so procured at least 90% of their calories by foraging; and a further 20 obtained 75 to 89% of their energy in this way. If the ethnography of contact-era New Guinea were better known, it seems likely that as many as 100 societies would be found to have depended for at least 75% or more of their calories on wild resources.

The project, ‘The Hunter-Gatherer Spectrum in New Guinea,’ has assembled ethnographic documentation on many of these hunter-gatherer groups and is currently analyzing what they tell us about hunter-gatherer lifeways and the implications for current theories of the foraging life. All of New Guinea’s hunter-gatherer groups depended for their main carbohydrate source on the starch of the wild sago palm (Metroxylon sagu). Sago is extremely abundant in its natural habitat; it has a high

energy density; and it demands little work to process (about 20 minutes is usually sufficient to supply an entire day’s calorie needs). These communities thus provide ethnographic analogies for understanding the lifestyle of foragers in energy-rich environments, an important contrast to the marginal environments in which most historically or ethnographically known forager groups were living.

New Guinea’s foragers can be divided into two major types according to the source of their meat protein. In the first type, meat sources were either very limited or primarily comprised of terrestrial and arboreal game – wild pigs, cassowaries, marsupials, rats, birds, and a large number of smaller fauna. In the second type, large amounts of meat protein were typically procured, primarily in the form of aquatic resources – in particular fish, shellfish, and sometimes crocodiles. Some groups in this latter type procured the majority of their aquatic resources indirectly through trade, usually in exchange for sago.

These differences in subsistence correlated strongly with differences in demography, social organization, and cultural forms.

Groups that procured limited amounts of meat protein or that relied primarily on terrestrial and arboreal game markedly resembled the classic hunter-gatherer societies typified by the !Kung, Inuit, Mbuti, and many Australian Aboriginal groups. At contact, their population densities were usually below 1/sq.km; their settlements were small, typically between 10 and 40 inhabitants; and they were mostly semi- or fully-nomadic, shifting residence every few weeks or months. Political life was relatively egalitarian: inequities in power and influence were uncommon, though fighting prowess, hunting ability, ritual expertise (including sorcery), and/or economic generosity brought prestige. Mobility was an important conflict resolution mechanism. Ritual life was comparatively unelaborated, and there was little visual art - though other aesthetic pursuits such as dance and song were sometimes highly developed. Contradicting a common stereotype that war is attenuated or absent among hunters and gatherers, fighting was endemic.

Groups that depended on aquatic resources rather than terrestrial and arboreal game typically exhibited a cultural complexity rivaling that of agriculturalists in New Guinea and they strongly resembled other aquatically adapted, hunter-gatherer societies such as the Native American communities of the Northwest Coast. Densities were significantly higher than among their terrestrially adapted counterparts, ranging from 1-6/sq km. Settlement size was usually on the order of one hundred to several hundred people, with some Asmat conurbations numbering well over a thousand. Settlements were relatively permanent, with lifetimes of at least three years and, more usually, a generation or more. Hierarchy was often pronounced, with some villages even exhibiting descent-group ranking. Male prestige was achieved in much the same way as among terrestrially adapted groups, but in contrast to the latter, leaders usually enjoyed a significant degree of power. Most of these groups also had developed highly elaborate ceremonial and visual art. Some, such as the Asmat, Karawari, Kwoma, and Purari are among the most famous of New Guinea’s ritual artists. Warfare was generally intense, and most of these groups were head-hunters.

One potentially important finding to emerge from this project is the overlooked influence of war on hunter-gatherer society and culture. The need to protect against attack by day and by night and to defend access to subsistence resources had strong effects on settlement patterns, social group formation and complexity, and ceremonial and ritual culture.

Hunter-gatherer scholarship has largely overlooked the importance of war, partly because of long-standing assumptions that warfare is a relatively recent emergence in human history and that hunter-gatherers lead a peaceful life. There is increasing evidence, however, that these assumptions are misplaced and that New Guinea’s

foragers may more accurately represent the hunter-gatherer past. Recent primate research finds that chimpanzees practice a form of lethal aggression against neighbors that has striking similarities to ambush in human society. This suggests that organized deadly violence may antedate the human-chimpanzee split, some 5 to 7 million years ago, and therefore may have characterized the whole of human prehistory. This conclusion is corroborated by historical research on reputedly peaceful hunter-gatherer groups such as the !Kung, Inuit, and Australian Aborigines, which suggests that war was considerably more prevalent among these peoples than previously supposed.