East Greenland

Leigh Stearns

Introduction

Mass from the interior of the Greenland ice sheet is transported to the ocean by numerous large, fastflowing outlet glaciers. Changes in the flow configuration of these outlet glaciers modulate ice sheet mass balance and sea level. Recent estimates show that Greenland's contribution to sea level has more than doubled in the past decade, increasing from 0.23 ± 0.08 mm/yr in 1996, to 0.57 ± mm/yr in 2005, and that the majority of this mass loss is due to changes in the flowconfiguration of a few large outlet glaciers (Rignot and Kanagaratnam, 2006; Stearns and Hamilton, 2007).

Ocean tides are known to affect the flow of glaciers terminating at tidewater [e.g. Lingle et al., 1981,

Meier and Post, 1987; O’Neel et al., 2003] and may provide an important control on calving and

subglacial melting by repeatedly circulating water beneath floating tongues [Motyka et al., 2003].

Boundary conditions at the frontal margins of tidewater glaciers provide important constraints on the

balance of forces affecting ice flow and iceberg calving. For many large outlet glaciers in Greenland, the boundary condition at the calving front (floating vs grounded ice) is not well known, owing to limited knowledge of ice thickness and fjord bathymetry. Additional data is necessary to improve ice sheet models and sea level rise predictions.

The interaction of tidal forces and ice flow varies depending on grounding conditions. Some glaciers show speed minima and uplift maxima when tides are highest, while other glaciers exhibit an opposite or more complicated response. The phase relationship between tidal height and glacier speed provides insight into basal processes for parts of glaciers where direct measurement and observation are challenging. We propose deploying high-rate GPS equipment at the front of Helheim Glacier to examine the effect of ocean tide on ice flow. Preliminary data, collected during our 2006 field season on Helheim Glacier, demonstrates the utility of high-rate GPS measurements for isolating tidally-modulated patterns in the x,y,z components of ice flow (Figure 1).

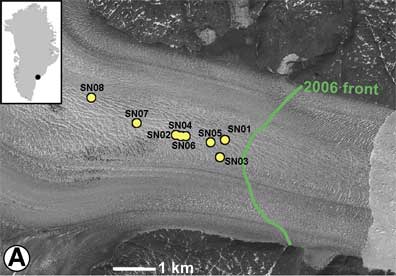

Figure 1: a). Location of GPS receivers deployed during the 2006 summer

season. Each station collected data for ~5 days, at 5 second resolution.

For the 2007 summer season, we propose installing the GPS stations in a

5 km x 5 km grid near the front of Helheim Glacier for several weeks.

b). Processed GPS data from site SN03 on July 23, 2006. In each panel,

the mean displacement for the day has been removed. Flow parallel shows

ice motion down flow (left to right), and flow perpendicular is across

flow motion.

In 2006, calving front data was only collected for discrete 4-5 day intervals. In 2007, we plan to collect GPS data near the glacier front for ~2 months, which will allow us to quantify the effect of small perturbation (i.e., tides) on the flow kinematics of the glacier.

Research Objectives

High-rate (5 second sampling) GPS measurements are necessary to determine tidal effects on ice flow. In addition to deploying ~10 GPS instruments near the calving front of Helheim Glacier, we will also deploy a tide gauge in the fjord ~5 km from the calving front. High-rate GPS measurements will enable us to quantify the effect that small perturbations at the calving front have on ice flow kinematics of the glacier. Specific questions we plan to address are:

- How sensitive is ice velocity to tidal fluctuations?

- How does the tidal signal propagate up-flow? If there is a time lag, what does this tell us about the flow dynamics and basal condition of Helheim Glacier?

- Does the relationship between tidal fluctuations and ice velocity change through the summer season? Is there a change in the relationship after a calving event?

References

Ekström, G. et al. 2006. Seasonality and increasing frequency of Greenland glacial earthquakes, Science, 311.

Lingle C.S. et al. 1981. Tidal flexure of Jakobshavns Glacier, West Greenland, Jnl. Geophys. Res., 86 (B5).

Meier, M.F. and A. Post. 1987. Fast tidewater glaciers. Jnl. Geophys. Res., 92 (B9).

Motyka, R.J. e al. 2003. Submarine melting at the terminus of a temperate tideater glacier, Ann. Glaciology, 36.

O'Neel, S. et al. 2003. Short-term variations in calving of a tidewater glacier, Jnl. Glaciology., 49:167.

Rignot, E. and P. Kanagaratnam. 2006. Changes in the velocity structure of the Greenland Ice Sheet, Science, 311.

Stearns, L.A. and G.S. Hamilton. 2007. Rapid volume loss from two East Greenland outlet glaciers quantified using repeat stereo satellite imagery, Geophys. Res. Letters, 34.