Proposal (PDF)

Project setup. Kurt writes:

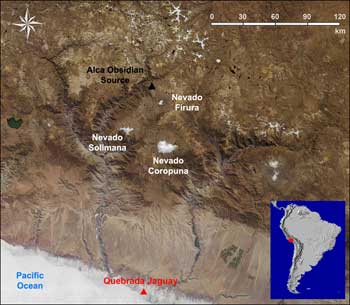

Before Dave and I can even think about the canyon survey itself, we have to deal with some serious logistical issues. We are setting out to spend three weeks backpacking and documenting archaeological sites within a 100 km-long canyon beginning near sea level and finishing at ~3,800 m above sea level (masl). Although we have been studying GoogleEarth, topo maps, air photos, and ASTER satellite images in preparation for the trip, we really have no idea what this canyon is like. There are some roads or footpaths that access the canyon at intermediate points along the route, but are they passable? Will there be water flowing in the quebrada while we are there? Is the canyon even a viable route from the coast into the highlands? It is difficult to know what challenges lie ahead, yet finding out the answers to these questions is really what the trip is all about.

As the only substantiated link between specific Pacific coast and Andean highland locales in the Terminal Pleistocene, the Quebrada Jaguay-Alca link provides a unique opportunity to learn how the high Andes were first explored and settled. We are putting ourselves into an archaeological simulation of sorts, seeing what the environment is like and what resources are available along a coast-highland altitudinal transect corresponding to the Quebrada Manga route. The Quebrada Manga is the optimal route in terms of shortest distance, but was it the route actually used by Paleoindians 13,000-11,000 years ago?

The first major issue turns out to be water, or the serious lack of it. As we travel by bus along the Panamerican highway from Lima to Arequipa, we see to our great dismay that there is no water flowing in the lower quebrada bed. This, combined with the 90o F temperatures typical at the coast this time of year, tells me that we can’t count on there being any water in the canyon at all. An adult hiking in rugged desert terrain such as this needs to drink several liters of water per day, and Dave and I plan on being in the canyon for about 20 days – that’s a lot of water, way more than either of us will be able to carry. We will have to cache food and water at regular intervals along the canyon route so that as we move along we will reach new supplies. This means that before we can begin the canyon survey itself, we need to spend about a week putting in food and water caches, and for this purpose we hire a 4x4 from our good friend Saúl Cerón at Inca Tours Peru, an outfitter in Arequipa. So after a trip to the local grocery store in Camana, we load the 4x4 full of food and about 60 5-liter jugs of water! Now we just hope we can access the canyon with the truck. Our topo map shows several roads or trails which access the canyon from modern highways to the south and east along the route. This should be simple, right? Wrong!!!

Whether the modern irrigation of the coastal plain west of Camana has accelerated sand dune formation, or whether the constant onshore winds have always caused these dunes to form, dune fields and erosion of the coastal hills have swallowed up the roads leading inland from the coast. We try lead after lead, asking locals, only to find that none of the roads shown on the topo map now exist. This is bad, for if we cannot drive into the canyon to put in caches, we will have to backpack them in many kilometers over very rugged, sandy desert hills. One evening we are able to follow a rough, narrow road inland for several miles, only to find that dunes are overtaking this route as well. We get out shovels and clear the road of sand, proceed for a kilometer or so, then we are stopped once again by another sand dune. We work into the night, digging out the road by the headlights of our 4x4, make it further inland, but just as it seems we have broken through, we encounter larger and larger impasses. Finally, it seems futile. Exhausted and defeated, we make camp in the roadbed. Though we have worked for hours to get inland, we can still hear the sound of ocean waves rolling in the distance.

The next day is better. We discover a good unimproved road leading inland from the Camana city dump, and though we get the vehicle stuck in one stretch of deep, fine volcanic ash deposits, we are able to chock the wheels with rocks and use our shovels to work the vehicle through. This road gets us about 35 km inland and connects us to a small homestead situated near a permanent spring within the Quebrada Manga – an oasis! Following the quebrada bed north from this place, we place a second water cache at the 50 km mark. Two caches down! Caching food and water is not an easy process – we have to be wary of animals that will steal our food or cattle that may trample and break our precious water jugs. We also do not want to take the chance that people will find our supplies and take them, so the best strategy is to bury the caches in an out-of-the-way place and collect GPS coordinates so we can be sure of finding our caches when we come back through this way on the survey.

The next day we drive back out of the Manga Canyon to the coast, head east along the Panamerican highway, and head up the massive Majes canyon toward the highland village of Chuquibamba, our endpoint for the Manga survey. We try in vain to find a road that will access the Quebrada Manga some 15-20 km to the west, but only footpaths head that way. Water is readily available in this part of the highlands, and the frequent Andean rains at higher elevations during this time of year should eliminate the need for us to cache water. We backpack our food supplies west from Chuquibamba following a section of an Inka road, and hide a cache under a rock overhang in a small tributary canyon before heading back to Chuquibamba and arriving after dark. We would later refer to our long backpacking day as the “Chuquibamba Death March”! No matter – with the hard part over, we now had all our supplies in place and we were ready to head back to the coast and get dropped off to start the survey.