Petroglyphs. David writes:

During the morning, as we waded through the reactivated river, we had renewed excitement knowing our focus of the day. Heading back to camp the previous evening, Kurt discovered a large boulder engraved with intricate carvings or “petroglyphs,” a form of rock art. Throughout the morning we identified more than 20 boulders with petroglyphs. The images included geometrical shapes, zig-zags, llamas, birds, pumas, snakes, foxes, human figures, and faces. Although the rock art probably dates to only the past few thousand years, the discovery of this site is quite important in regional contexts. Future investigations of the petroglyphs and the people who created them will be pursued in coming months

The Inka Tambo. David writes:

For the past week we’ve been making our way into the highlands surveying the canyon rim towards the settlement of Llacas. Most of the day we spend walking along a road of smoothed flagstones, indiscernible from most of the other rocks except that they are worn white. This white road is testament of the first statehood to unite most of the lands of the Andes, the Inkan Empire. We know we are not the first travelers along this canyon as the path we follow was smoothed by ancient peoples, countless llama trains bringing goods from the coast to the highlands, Inkan armies and messengers, and today the few farmers and llama herders that live in the local canyons around springs and wells.

Before the project began, back in the Andean Archaeology Lab in Orono, we traced our route using the program GoogleEarth. From the satellite images we located large rectangular structures and corrals on top of the canyon near Llacas. Our Inka road was leading us to it. The day we were close to our third supply cache, we finally came across the structures. The series of lodging rooms, storage houses and corrals is what is called an Inkan tambo. Tambos can be found along Inka roads in modern-day Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Colombia, and served as administrative and military centers for the Inkan Empire.

Descent to Chuquibamba. David writes:

The two days before leaving the canyons, we were finally hit by rain. We were in a side quebrada exploring rock shelters, as the desert rain fell and made the once dry rocks sheen and glow in the sunlight. We soon realized the difficulties the rains created as the small quebradas we were exploring became roaring impassible rapids and waterfalls. Since our only water source was the roaring streams, our water for the rest of the project was filled with thick brown and black sediment. We had to let the water sit overnight to let the sediment sink to the bottom, then begin the long process of filtering the water numerous times using a t-shirt, and boiling the water over our small camp stove.

It was still raining on our last day in the canyons, yet we still had a morning of survey work to be happy about. On our way to the

town of Chuquibamba, we explored a set of rock shelters set in one great ridge. Unfortunately, the preservation of the shelter floors

makes it unlikely any evidence of Paleoindians would be preserved if they indeed utilized the rock shelters. Instead, evidence on the

surface of the sites included ceramics of the local Chuquibamba Culture and the subsequent Inkan influence.

The rest of the day we hiked closer and closer to civilization, the town of Chuquibamba. Going down the ancient paths and switchbacks from the canyon rim to the town was a surreal experience as a mist and fog set in among the large cacti that hugged the slopes. The obscuring fog made it impossible to see more than ten meters ahead, yet from below we heard traditional Andean music floating up from the town assuring a hot meal and comfortable bed after weeks in the desert canyons and highland pampas.

Project Summary

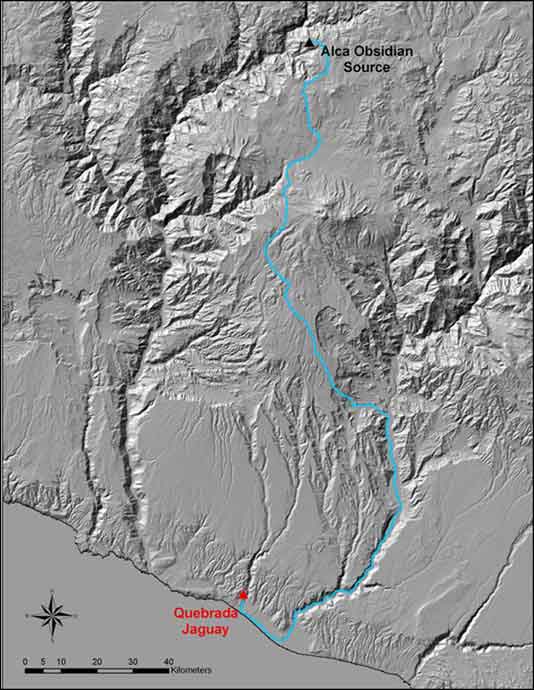

Our experience traveling through this canyon suggests that the Quebrada Manga was not an ideal travel route from the coast to the highlands for the early settlers of southern Peru. We could never have known this without on-the-ground exploration of the Manga canyon, and this finding is actually quite significant. The route from the Terminal Pleistocene coastal site Quebrada Jaguay to the highland Alca obsidian source probably followed the massive Majes canyon to the east – a longer route, but a well-watered, resource-rich valley.

Short-distance moves from Quebrada Jaguay into the lomas zones were probably designed to take advantage of valuable plant resources and to hunt deer, camelids, and other fauna. Our identification of relict Caesalpinia spinosa tree stumps (Dillon, personal communication) suggests that until recent overgrazing and deforestation, the coastal hills were covered by a lomas woodland. Paleoindians probably found these coastal hills to be a lush, productive zone relative to today’s degraded environment.

Longer-distance moves from the Quebrada Jaguay locale to the Majes valley to the east probably brought early inhabitants within the zone where petrified wood crops out. The Majes valley would have afforded year-round fresh water, freshwater prawns, fish, and other fauna, and tuna (Opuntia sp.) and other fruits. Tuna seeds, as well as freshwater prawn shells, have been identified within strata at Quebrada Jaguay, lending support to this idea. Recently, we have used GIS to model a least-cost path between Quebrada Jaguay and the Alca obsidian source, and the path follows the Majes canyon north, passes west of Chuquibamba, and continues over the highland plateau between the Coropuna and Solimana ice caps. Ongoing archaeological work along this modeled least-cost path will be aimed at discovering additional Paleoindian sites in the various ecozones so that we can better understand the mobility, settlement patterns, and environmental adaptations of some of South America’s earliest settlers.